A Cultural Journey as a Leeds University Student in East Germany, 1986.

Introduction

From 1984 to 1988, I studied German Language and Literature at the University of Leeds. In my second year, I spent twelve weeks at the Karl Marx Universität in Leipzig, East Germany, and in my third year I worked as an English language assistant at a grammar school in Pirmasens, West Germany.

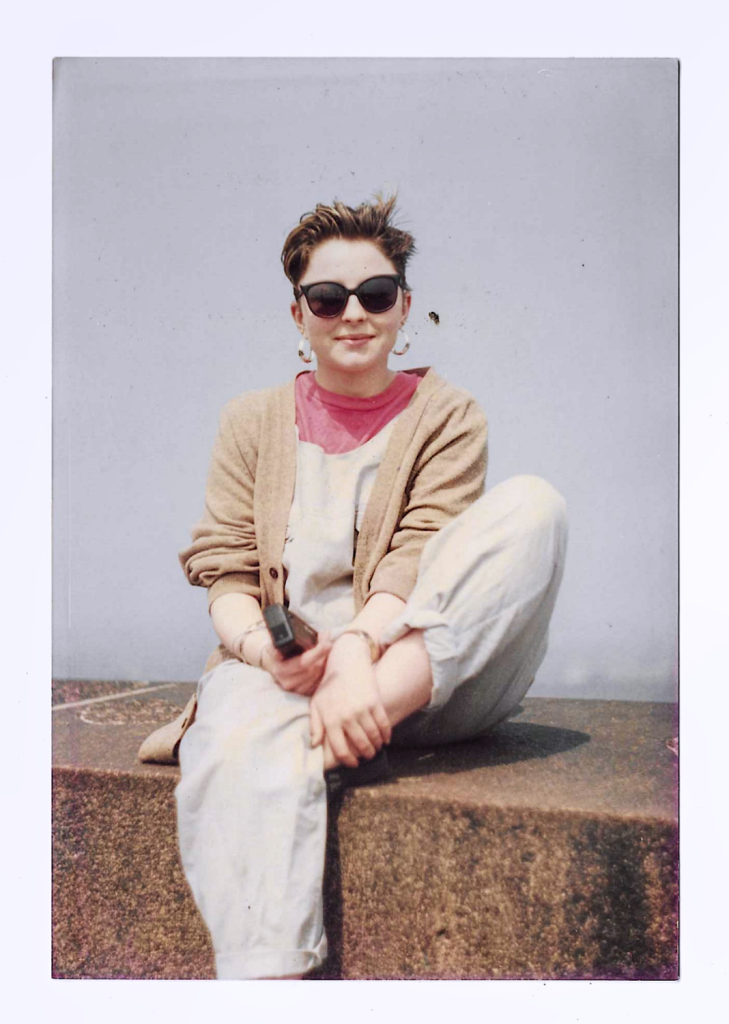

The Leipzig stay was part of a cultural exchange between the Karl Marx Universität and the German departments at Leeds and Manchester. About fourteen of us went altogether: ten from Leeds, four from Manchester. Two of my friends, Trasy and Vonny, were with me (the three of us would go on to teach English in Japan after graduating in 1988).

I kept a journal from April 1, 1986, when we set off from London’s Victoria Station, until June 20, when I crossed from East to West Berlin at the infamous Friedrichstraße checkpoint. That journal — along with a box of DDR memorabilia and photos — has stayed with me for all the years since. Now, almost 40 years later, sitting in my mountain home in Dominica, I’ve decided to revisit it: to write an account of three unforgettable months of my life.

At the time, my understanding of East Germany was naïve and superficial. There was no Internet back then, so resources were scarce, and the Cold War added a dimension you could only read about in Le Carre novels. The deeper truth only began to emerge in 1989, when the Wall came down. But even in its limitations, I think this diary offers a snapshot of what it was like for Western students to live, study, and wander about in Leipzig and beyond in the mid-1980s. Reading, writing, going through old photographs, and reconnecting with some of the people who were there have all brought it back to me.

East Germany - the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR) – existed from 1949 to 1990 as part of the Soviet-dominated Eastern Bloc. Governed by a single political party, the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED) and backed by the Soviet military, it was tightly controlled and heavily surveilled. From 1971 to 1989, the DDR was led by Erich Honecker: once imprisoned by the Nazis, later one of the architects of the Berlin Wall, and the man behind the infamous “shoot to kill” order for border guards. (He was indicted for mass murder in 1990, but never stood trial due to failing health, and died in exile in Chile in 1994.)

Meanwhile, the world was shifting. In Moscow, Mikhail Gorbachev was introducing Glasnost and Perestroika. In London, Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister; in Washington, Ronald Reagan was President.

Growing up in a South Yorkshire mining village, I’d witnessed the social impact of the 1984–85 strike. By the time I arrived at university, I was a fledgling socialist – like many students at the time – and I took part in marches and protests against the Thatcher government, South African apartheid and more. I also signed up for an optional Marxism seminar run by the German department, and, though I had no previous journalistic experience, I was keen to get into it, and began writing film and theatre reviews for the Leeds Student newspaper under editors Helen Slingsby and (later) Jay Rayner. University had afforded me an opportunity to discover what I was all about.

When the time came to choose where to spend my second year study term abroad, several attractive West German universities were on offer. But when I saw Leipzig’s Karl Marx Universität on the list, there was no question about it. I would spend three months studying in the DDR, followed by the whole of my third university year working as a teacher in the Rhineland-Palatinate.

I spent the last weekend of March 1986 at my parents’ home in Doncaster, packing and preparing for the trip. On the morning of April 1, my father drove me to London. I was ready to step behind the Iron Curtain.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week One.

London to Leipzig

At 7am, Victoria Station was not yet crowded with commuters. My father and I walked across the concourse and checked the departure board for the platform for the Dover Western Docks train where we found my friends waiting. He wished me a good trip and I watched him walk back the way we had come.

I had a rather battered leather suitcase that was filled with clothes and the things we’d been told in preparatory meetings at Leeds would be ‘useful’ — mainly toiletries and toilet paper. Slung over my shoulder was my small canvas student bag with passport, money, notebook and pens, a Sony Walkman, spare batteries, and a bunch of cassette tapes (Everything but the Girl, Lloyd Cole and the Commotions, Orange Juice, Talking Heads, Style Council). I also had two books: Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse 5.

I greeted my friends Trasy and Vonny, the other Leeds students who I didn’t know so well, and introduced myself to the Manchester group. Everyone seemed nervously excited. We boarded an old carriage, already forming groups – friendships that would endure throughout the trip. With a jolt, the train pulled out on time at 7.30. We were on our way.

The chatter continued as we chugged across the English countryside. Carriage full of laughter, bellies full of butterflies, luggage full of toilet rolls, I wrote. At Dover Western Docks, we boarded a Channel ferry bound for Ostend, Belgium. Once there, we struggled to find space on the train to Cologne as a German school trip seemed to have taken up every seat. “Alles reserviert!” a rather formidable school mistress barked at us as we dragged our luggage for what felt like the entire length of the train before we finally found space to crash. By the time we reached Cologne, tiredness and hunger were setting in, and we were relieved to find a bratwurst stand on the platform where we waited for a train that was bound for Hanover and eventually Leipzig.

When it arrived, we were instructed by a station master to occupy the carriages in the rear-half of the train as it would be split on arrival in Hanover. The carriages were the grubbiest any of us had ever seen. The dark upholstery was threadbare and looked like it hadn’t been cleaned in years, and the windows were covered in a film of dirt. By now far too tired to care, we made ourselves as comfortable as we could. I think we must have had the whole of the rear end of the train to ourselves.

By the time we pulled into Hanover station, darkness had fallen and most of us were dozing – we’d been travelling for about twelve hours. The train shunted backwards, then forwards again, presumably shedding carriages and receiving a new locomotive. A guard walked through our carriage, confirming with us that we were indeed staying on board. His confused and rather alarmed expression made me feel uneasy – as if we were going on a journey that nobody in their right mind would ever take. He wished us good luck and left. Doors slammed, a whistle blew and, with a jerk, the train left the station, moving eastwards and deeper into night. I watched the darkness through the murky windows for a while, Trasy slumped against me, her eyes closed but unable to sleep properly. I too tried to get comfortable, willing sleep to come.

At around 4am, the train stopped at the brightly illuminated Marienborn station, one of the most important border crossings between West and East Germany. It was manned by employees and soldiers of the DDR, at times said to number more than 1,000, and included rail and road crossings. The road was the main vehicular transit crossing from West Germany to West Berlin. The border crossing had an underground tunnel system, a power plant, a currency exchange, and even a mortuary. But at the time, I don’t believe I was aware of any of this.

“Ausweise!” announced a fierce-looking woman in an ill-fitting, lime green uniform. “Ausweise!” she repeated, loudly and impatiently, as we all stirred from our uncomfortable slumber and dug out our passports. As she scrutinised our permits and visas, and then stamped the passports, she handed us forms to fill out (that she never collected) and then told us that our music players were not allowed in the DDR and must be confiscated. We objected, doubting it was true, and her demeanour grew uglier. There was lots of chaotic and confusing shouting and pointing from both her and her colleagues who now filled the carriage bringing more menace, lime green, and guns. After verbal salvos that we were having difficulty understanding and keeping up with, and which really didn’t seem to have any point other than to demonstrate their dislike of us, they promptly marched out of the carriage, slamming the door and leaving us wondering what on earth would transpire. We waited, now awake and alert enough to hide our music players and anything else we thought might be taken. For an eternity, it seemed, absolutely nothing happened. The train just sat under the bright lights of the Marienborn station in silence. Then, unexpectedly, there was the sound of doors slamming and the train began to move off. Just as we dared to breathe sighs of relief, the carriage door slid open once again, and we were momentarily filled with dread. This time, however, the lime green uniform was worn by a young woman with a friendly smile who asked to see our train tickets and then left. We were, it seemed, now behind the Iron Curtain and travelling into the east.

Not too long after the border crossing, the train stopped at another station. It was dimly lit, but through the grimy windows I could make out a sign for Magdeburg. I wasn’t sure where it was, or how far away we were from our destination, but I noticed that people were getting on board. This happened at several further stations along the line, and it wasn’t long before the early morning sunshine revealed to us that the train had become rather crowded with, I assumed, commuters on their way to Leipzig.

Through half-open eyes, could sense them staring at us, though they quickly turned away their gaze when I looked back at them. We must have been a surprise; a curiosity. Perhaps even unwelcome. I was tired and tried a few weak smiles, but no-one smiled back. I wondered if they disliked us as much as the border guards, or were shy, or maybe even afraid. Thinking about it later, it would have been foolish for any of them to engage with us as there were spies and informants everywhere.

At 7.36am, almost exactly 24 hours since we left London Victoria, our train pulled into the huge and imposing Leipzig Hauptbahnhof.

In at the Deep End

We piled out of the train and onto the platform where we were met by Dr. Johannes Hentschel, Professor of Political Economy of Capitalism at the Franz Mehring Institute of the Karl Marx Universität in Leipzig.

After the briefest of greetings, we were bundled into waiting Trabant taxi cabs outside the station and driven to the student ‘Wohnheim’ on Tarostraße in the south of the city. It was a large, drab box of a building that was used exclusively as student accommodation. There, we were split up and allocated rooms. Except for David (a Leeds University student) and I, who shared a rather spacious room, everyone else was allocated small bunkbed dorm rooms which they shared with a DDR student. Why David and I weren’t given the same treatment was never explained. Our third storey room faced the southwest and overlooked a sports field. The windows were coated in a film of brown, caused by emissions from a nearby lignite power station.

Despite our obvious collective tiredness, we were given a mere 30 minutes to freshen up and be ready to leave. We were then driven to the university and taken to the Mensa, a large canteen, where we had a breakfast of wurst (liver sausage), bread, and sauerkraut.

After a brief orientation of the department where we would have our classes, we were taken to the police station to officially register and receive our student ID cards. The form-filling and police interviews took an eternity, and a lack of sleep made it all rather harrowing. After so long without proper sleep, our nerves were frazzled. When it was finally over, we were taken back to the university for further orientation before being granted a couple of hour’s rest at the Wohnheim.

In the evening, we were driven to the Moritzbastai for welcome drinks with Dr Hentschel and some of the other university academics who would be tutoring and accompanying us on cultural outings over the next three months.

The Moritzbastai was a fascinating place, and we would spend further evenings there during our stay. Constructed between 1551 and 1554, it was part of Leipzig’s city fortifications. Over the centuries it served as warehouse, prison and barracks but was destroyed during the second world war. In the 1970s, Leipzig University students rediscovered it and began its restoration (one of the students was Angela Merkel who, in later life, would be Chancellor of a reunited Germany).

It officially opened in 1982 and became a hub for student cultural and social life. It was also a venue for discussions, presentations, and performances — often rather subversive. The second time we went there, we were invited to attend a presentation on a free Palestine by members of the former Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO). Other cultures and political representation were also present, and we had interesting evenings with students from Yemen, North Korea, Cuba, Afghanistan, and other countries of the Soviet Bloc such as Poland and Hungary.

On this evening however, after 24 hours of train travel followed by a long day of university orientation and red tape, we were far too exhausted to appreciate the place. We did our best to engage, but we were all really struggling to keep our eyes open.

I found myself cornered by Dr Hentschel who was speaking to me in English, in between chain-smoking cigarettes. It was difficult to warm to him. His physical appearance and his conversation didn’t help — greasy hair and skin, large glasses, ill-fitting, drab clothes that seemed to be made of stiff nylon or polyester, and an unmistakable, sour body odour. He seemed to be especially interested in the girls, probing me for information about them. I told him we had all been close friends for many years, aiming to make it clear we were a solid, tight-knit group. He came across as seedy and rather too interested in our personal lives.

Years later, after reading accounts of life under the East German regime and the tactics of Stasi interrogators, I wondered if my sleep-deprived grilling had been deliberate. I guess I’ll never know.

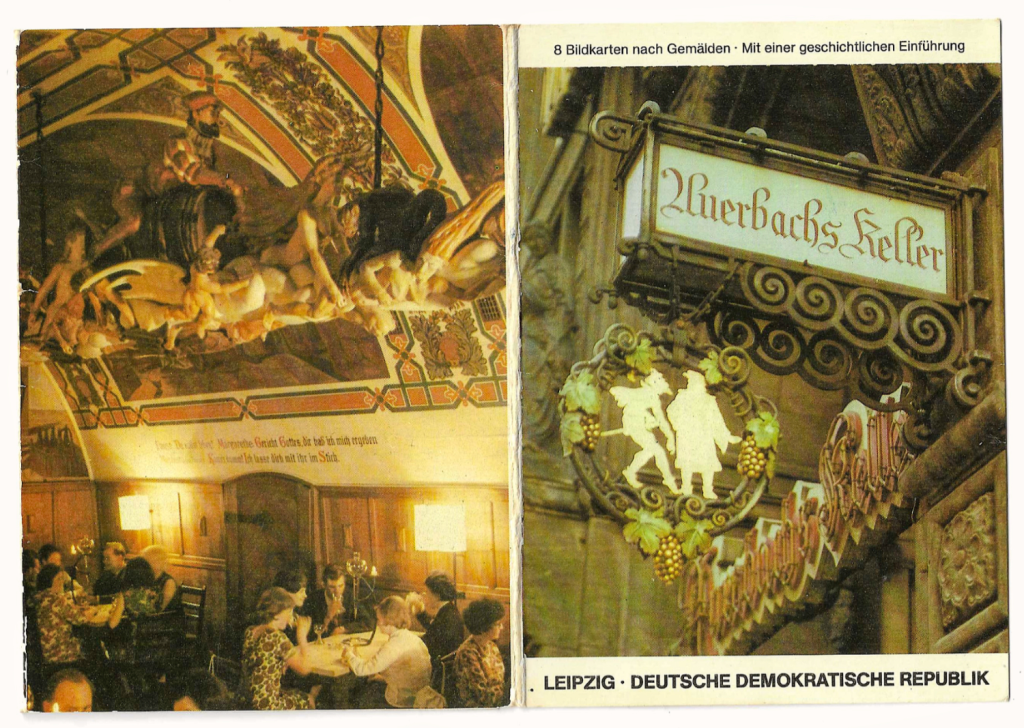

We spent the first week in Leipzig rather like university freshers. Although we had a weekly schedule of classes and organised excursions, we also had plenty of free time and were allowed to wander wherever we wanted, thankfully unaccompanied, though undoubtedly observed. We made the most of this relative freedom, exploring the city and dining for three straight evenings at the iconic Auerbach’s Keller.

Auerbachs Keller (Auerbach’s Cellar) is the most historic and famous restaurant in Leipzig. It was first mentioned in 1438 and became well known in the 16th century when the doctor and humanist Heinrich Stromer von Auerbach opened a wine tavern in his vaulted cellar. The playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was a student in Leipzig between 1765 to 1768 and often frequented the tavern. He later immortalized it in his drama Faust, making it the setting for one of the play’s most famous scenes – where Faust and Mephistopheles drink with rowdy students.

In modern times, Auerbachs Keller became both a functioning restaurant and a cultural landmark with its atmospheric, vaulted rooms decorated with murals depicting scenes from Faust. Outside the entrance on Grimmaische Straße, bronze statues of Faust and Mephistopheles stand welcoming guests.

One of the waiters there – Louis Ratz from Budapest – invited me to have a look at the restaurant kitchen where he quickly took the opportunity to tell me that he wanted to change money and offer me his daughter’s hand in marriage. I politely declined. We’d been told there were serious penalties for changing money on the black market and I didn’t want to risk getting booted out of the country in my very first week. As for his daughter, I explained to Louis that fourteen was a little too young for me.

It seemed that devilled pork with potatoes and pickled cabbage was either a house specialty or all they had. But it went down fine with a few bottles of Hell beer. No kidding.

After the Louis Ratz incident, we thought it best to expand our dining horizons, which led us discover that feeding ourselves was going to be a challenge. There were always lines at restaurants, coffee and food shops and, by the time you made it inside, there wasn’t very much left.

There was a small supermarket near the Wohnheim that had nothing left on the shelves by around 10am – though there was never that much to begin with. We would take turns to get there early to buy wurst, bread, beer, and newspapers – Neues Deutschland and Leipziger Volkszeitung - and then eat together picnic style on the sports field behind the Wohnheim, where we could enjoy some personal space and where it would also be more difficult to eavesdrop our conversations.

We had already formed small groups who hung around together. I rarely saw my roommate, David, who seemed to be trying to forge friendships with East German students, which I admired him for but which I feared may prove risky.

On Saturday morning, we were invited to attend a dress rehearsal for a production of Master Harold and the Boys by celebrated South African playwright, Athol Fugard. It was enjoyable, though at the time unknown to me and somewhat hard to follow. Like many of the cultural experiences we were to have during the next twelve weeks, we also discovered that it contained a shoe-horned political message. In this case, it was not just apartheid that was the enemy of the people, it was western decadence in general that had its boot on the necks of the oppressed. This was a rapid learning experience, and in many ways useful preparation for just about everything that was to come.

Other students also attending the dress rehearsal were from North Korea (all wearing blue blazers with button badges of Kim Il-Sung) and Yemen. One of the Yemeni students told me about a jazz club somewhere on the western outskirts of the city, and that there was supposed to be live music that night. I looked it up on one of the maps we’d been given and saw that we could catch a tram to the last stop and then walk about a mile. We were up for trying to find it. It seemed that jazz was undergoing a revival in the DDR and was considered by some to be ‘fashionably subversive’.

So, that evening our little group set off in search of some underground music. We walked into the city from the Wohnheim and boarded a tram that was travelling west. We were heading to the final tram stop at Schkeuditz and then we would have to walk to Dölzig where the club was supposed to be located. The journey was like being in a time machine. Though hardly a bright shining city centre of modernity, Leipzig’s Alt-West suburbs by comparison looked like they were still in the 1940s. Street lighting was scarce, and the evening gloom suffocated these bleak and tired looking neighbourhoods with their grey buildings and dark, narrow alleyways.

The tram reached the end of the line and, after consulting the map, we walked along a long tree-lined road until we eventually stumbled on the Jazz Club. At the door, we were told that the event was ‘ausverkauft’ (sold out) and that we were not allowed entry. We were unsure whether this was true, or whether it was simply too risky for the club’s manager to let us in. I tried to imagine his surprise at opening the door to a group of western students. Disappointed, we began walking back through the darkness to the tram station.

After a short distance, we could hear a heavy rumbling noise that seemed to be getting closer, though we could see nothing at all. It was definitely mechanical, the sound of machinery, very heavy, and very loud. Suddenly, out of the gloom, a tank appeared. But not just one. Right on top of us, before we knew it, came a seemingly endless convoy of Russian tanks and military vehicles packed with soldiers. The noise was deafening — we were yelling but couldn’t hear each other — and the ground was shaking almost as much as we were.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Two.

Student Life

In the main, our academic subjects at Karl Marx Universität orbited around Political Economy of Capitalism and Socialism, Marxism and Leninism, Language and Literature, and Landeskunde – regional studies that included at least one weekly outing.

Our Political Economy of Capitalism and Socialism class was led by Herr Schaeffler, a young and pleasant guy who was happy to discuss a range of subjects with us and compare how they were viewed by the east and the west. I’d heard that most academics were also party members, so it was unclear just how open a conversation we would have. In the end, it didn’t really matter, as the class became dominated by a small but vocal group – around four or five from both Leeds and Manchester – who seemed dead set on criticising everything DDR. Theirs was an uncompromising view of the world; west versus east, good versus bad. So, there was no proper conversation; they just shouted down Herr Schaefler who often appeared to shrug and give up. I found it embarrassing. Looking back, I can forgive them, I guess, for I too had a rather poor understanding of geopolitics when it came to the Soviet Bloc. But I’d like to think I was open-minded enough to hear opinions from both sides of the wall. It was disappointing as the class had the potential to be interesting.

Language and Literature was my least favourite class. I found East German authors difficult to connect with and the language was heavy going. Besides, I was busy re-reading Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four which was far more interesting given my situation.

This led to an unexpected incident in the Mensa one lunchtime when someone spotted the novel in my hand as I was lining up for food. This person – I’ve no idea who he was, or whether he was a student or a tutor – began shouting and hurling insults at me. Everyone stopped what they were doing and stared. I didn’t know what was going on until he pointed to the book, ripped it from my hand and marched away with it, still shouting at the top of his voice. I stood there stunned and bemused while the others looked at me in shock. Nineteen Eighty-Four, it transpired, was a banned book. When I asked Dr Hentschel about the incident and the reasons for banning the book, he just smiled and offered no comment at all. So, I retreated to my second book, Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse 5 and wondered if Orwell had been incinerated or was now being shared by an underground movement of university academics. So it goes.

Landeskunde (regional studies)

Our first Landeskunde excursion was a cultural tour of Leipzig beginning with a trip to the historic Thomaskirche. It has an interesting history, going back to the 12th century. Martin Luther preached here on Pentecost Sunday in 1539, Johann Sebastian Bach was director of music here from 1723 until his death in 1750, Mozart played the church organ here in 1789, and Richard Wagner was baptised here in 1813. Completing the classical music connection is Felix Mendelssohn who lived in Leipzig from 1835 until his death in 1847, and there’s a statue of him opposite the church. The Thomaskirche houses the tomb of Bach.

After our first excusrsion, Trasy, Vonny, Cate and I wandered the city centre, taking in all the flags, banners, and agitprop messages that were being erected and unfurled in preparation for the XI Parteitag (party conference) of the SED. Wherever you looked, socialist messages screamed back at you in vivid red and white.

“Vorwärts Zum XI Parteitag der SED!”

(Forwards to the 11th party conference of the SED!)

“Alles für das Wohl des Volkes und den Frieden!”

(Everything for the wellbeing of the people and for peace!)

“Je starker der Sozialismus, desto sichere der Frieden!”

(The stronger the socialism, the more assured the peace!)

“Mit der USSR im Bruderbund!”

(With the USSR in brotherhood!)

Continuing the thread of Martin Luther, the second Landeskunde excursion this week was to the historic city of Wittenberg. For this, we were accompanied by Dr Hentschel who gave us a detailed tour of its historic and cultural landmarks in light snowfall. The temperature had suddenly dropped, and we were all shivering. Nevertheless, it was nice to be out of Leipzig for the first time.

Wittenberg was overwhelming for me because I knew nothing of its history and far too little about the main actors involved. I think there was a level of expectation that we already knew a lot of this stuff so, for me at least, the tour was pitched at too advanced a level. I found it interesting, though it was hard to take it all in. I had, of course, heard of Martin Luther, but Melanchthon and Cranach were completely unknown to me, so visits to their former homes, and an appreciation of artwork and translated Bibles lacked sufficient context for me to appreciate it all as much as I ought to have.

After the tour, we were allowed some free time to wander, so Trasy and I went off photographing beautiful old buildings that, again, we probably ought to have known far more about.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Three.

The Development of the Human Personality

In our Political Economy of Capitalism and Socialism class, when he could get a word in, Herr Schaeffler said that the socialist revolution in the DDR required “die Entwicklung der Persönlichkeit des Menschen” (the development of human personality), which was his explanation of why all the agitprop, for example, was so inescapable, especially in advance of the SED Parteitag (party conference). The development of the mind, and personality, included a very Orwellian revision of national history (victims of Nazism were exclusively referred to as ‘antifascists’, for example, and the current DDR was populated by surviving antifascists), compulsory Marxist/socialist education, and a powerful surveillance system that would root out dissenters. These factors would ultimately result in a uniquely East German identity. At least, that was the plan. Some scholars believe that after the wall came down and Germany was reunified, those who had known nothing other than life in the DDR had difficulty adjusting to the new Germany precisely because of die Entwicklung der Persönlichkeit des Menschen.

In Landeskunde, Frau Sander, another tutor, accompanied us on a further Leipzig excursion – this time to the Bach Museum. Frau Sander was very likeable and she seemed genuinely far more interested in history and culture than political idealism and dogma. The one problem we had with her was, unfortunately, body odour. This was a thing in the DDR, and we assumed people either didn’t notice or had become accustomed to it. Soap and toiletries were of poor quality and scarce. When the supermarket near our Wohnheim did stock toilet paper, we discovered to our horror that it was rather like sandpaper. Close proximity to Frau Sander was most challenging in this regard. She was, however, extremely protective of us and I think we all thought fondly of her, despite the you-know-what.

Landeskunde: Kyffhäusergebirge

A second Landeskunde excursion would extend over the weekend. We were off to the southern Harz Mountains and the Kyffhäusergebirge in Thuringia, to the west of Leipzig.

We set off by train from Leipzig at 7.30am and I was lucky enough to sit with Wolfgang, a Polish journalist who was coming with us part-way. He was taking a course at the university and had been invited along by Frau Sander who he liked to tease.

“We’re all from the kindergarten and that’s our teacher,” he told the ticket-collecting conductor, pointing to Frau Sander who was seated with the rest of our group further down the carriage. Conversation with Wolfgang was whispered and fascinating. He explained to me what it was like to live in the DDR and how he had friends in Leipzig who were underground poets, and who he described as ‘anti state’. They lived under constant threat and fear of imprisonment, he said. But they were committed to freedom and undermining the regime. Wolfgang was convinced that the DDR could and would not endure. Just as he said this, the train entered a long tunnel and, as the carriages had no lights, darkness was all consuming. When the train re-emerged into daylight, Wolfgang was grinning from ear to ear. “Just like life,” he whispered. “Absolutes Finsternis” (complete darkness).

After a couple of changes, we got off the train at the spa town of Bad Frankenhausen where Wolfgang shook my hand and departed. I was sad to see him go as his conversation had been singular and enlightening. From the railway station, we were driven by taxis to a nearby campsite in the countryside.

Not really a holiday camp, it was spartan and functional with a shared dormitory and canteen. By now, it was mid-afternoon, and everyone was hungry. A meal of pork, potatoes, and pickled cabbage was served for us in the canteen which we shared with around 20 Russian soldiers who were stationed nearby, doing their national service. This seemed to mainly consist of harvesting potatoes for a local farmer. Most of them were from states in the far east of Russia, beyond Lake Baikal, and none spoke any English. Stockily built with Asian features and big, rough hands, these guys looked like they were accustomed to working outdoors (I later spoke with the farmer whose potatoes they were harvesting, and he told me they thought the campsite toilets were for washing the harvest).

One of our group, Gill, knew some Russian and helped us to chat with them. Conscripts serving two mandatory years in the military, they weren’t at all interested in soldiering, it seemed and were all terribly homesick. They wanted to know about England and were especially interested in talking about football which resulted in the challenge of a game.

One of the soldiers produced a football and, after our meal, a few of us played jumpers for goalposts – Leeds and Manchester versus the Russian military. They were the only ones with a team kit, naturally. Despite their size and big heavy boots, the game was fun, and we played until dusk. Thankfully, there were no broken bones. As for the score, well better not to ask.

While most of our group retired to the dorm, a few of us spent the early evening in the canteen drinking beer and playing draughts with the soldiers, who cheated terribly. The soldiers were not allowed to drink alcohol (they eyed it enviously) and had an early curfew, but the conversation, though linguistically challenging, was interesting and memorable. We never saw them again after that day, and I’d like to think that they remember it as fondly as we still do.

In the morning, after breakfast in the canteen, we waited for and then caught a public bus to the hills of Kyffhäuser where we began our ‘Wanderung’ – a hike to the summit of the 477m Kulpenberg hill. To fully appreciate the countryside and mountain views, we climbed to the observation deck of the 94m TV tower that stands on its peak. Despite the seemingly immovable early morning mist, the surrounding views were exceptional.

From Kulpenberg, we began a long and beautiful country walk along a forest trail that eventually brought us to Reichsburg Kyffhausen (Kyffhausen Castle) and the Kyffhäuserdenkmal (Kyffhäuser Monument, or Barbarossa Monument). Again, this was one of those moments when I really wished that I knew more, so that this fascinating and beautiful place had more context. It was engaging nevertheless, and I thought the grand stone carving of a seated Barbarossa was captivating.

The resident tour guide made much of the Bauernkrieg, the German Peasants’ Revolt of the 1520s against the ruling aristocratic dynasties, which resulted in the slaughter of 100,000 poorly armed peasants and farmers. To add a political spin to this event was an open goal for the guide and, even with still limited experience of DDR propaganda, by now, I fully expected the comparisons with Nazism and contemporary capitalist societies that inevitably ensued.

From Reichsburg Kyffhausen, we continued our forest hike and reached the impressive Barbarossa Höhle (Barbarossa Cave), a cavernous subterranean system of lakes and grottos. According to legend, King Barbarossa sleeps somewhere in the cave along with his knights and one day he will wake and restore Germany to greatness. I wondered what the guide’s definition of greatness might be but didn’t ask. In some versions of the legend, it was interpreted as German unification.

From the cave, we concluded our outing with a long hike all the way back to the camp at Bad Frankenhousen where pork, potatoes, and pickled red cabbage awaited us. We ate it gratefully, slumbering in the canteen, half-watching a dubbed German version of Bonnie and Clyde on a snowy black and white television set before sleepwalking back to the dorm.

On Sunday morning, we were up early for a wander around the ancient town of Stolberg. With a long history and known as the site of several battles led by Thomas Müntzer during the Bauernkrieg, Stolberg’s streets (notably Niedergasse) are lined with attractive timber-framed buildings that were spared from bombing in World War II, and its large hilltop castle dates to around 1200. Thomas Müntzer’s legacy was another which provided tour guides with a useful opportunity to emphasise those aspects which suited the Party message. We were told that, having rejected both the reformists and the Catholic church, Müntzer took sides with the peasants and led them in a fight against the ruling feudal authorities – rather like the antifascist Ernst Thälmann. Müntzer was captured after the Battle of Frankenhausen in May 1525, tortured, and executed. Thälmann was murdered by the Nazis at the Buchenwald concentration camp. These talks were not revisions of national history as such (as per Schaeffler’s Entwicklung der Persönlichkeit des Menschen) but they were certainly bent towards supporting the contemporary message of the Party.

From Stolberg we caught a train to the town of Sangerhausen. Though seemingly older and rather prettier than Stolberg, we had little time to linger before catching the day’s only connecting train back to Leipzig.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Four.

Political theatre

We had two trips to the theatre (Schauspielhaus) in Leipzig. The first was supposed to have been Goethe’s Faust – which we’d been looking forward to – but was switched to Goethe’s Egmont. The story of a martyr’s death in the face of despotic oppression, this was low hanging fruit for the emphasis of the plot becoming that of a political manifesto mirroring the struggle of socialism in the east against capitalism in the west. Not knowing much about the story beforehand, it became hard to distinguish between which parts of the drama where genuine and which were hammed up to reflect the Party message. It was interesting, but I think we would all have preferred Faust.

The second performance was Kafka’s Schloß. I’m a fan of Kafka’s work, so this was a treat despite the rather obvious allusion to the controlling systems of capitalism providing the backdrop for K’s alienation and attempts to achieve an unobtainable objective. Having studied the piece beforehand, the DDR twist to the story was much clearer to me than it had been for previous cultural experiences. But rather than annoy or irritate, I found it fascinating, and I wondered if all theatrical performances in the DDR were selected based on their storyline and the ability to introduce the political message. Shaeffler’s words were inescapable: die Entwicklung der Persönlichkeit des Menschen. Clearly every experience in the DDR was designed to achieve this aim.

Our little gang continued to eat out as much as possible for it was clear that the little shop by the Wohnung on Tarostraße sold nothing but wurst (liver sausage), and then only if you turned up when it opened. The student Mensa was the next last resort as the food there was especially uninspiring, yet we’d found it difficult to find anything other than devilled pork, potatoes, and red cabbage on any restaurant menu. I was beginning to forget what fish and salad looked and tasted like. Incredibly, there wasn’t even any chicken which seemed really odd. Were chickens decadent or simply saved for the Party hierarchy? But we could live with it. There was, it seemed, an endless supply of Hell beer to wash it all down.

The Parteitag had reached its zenith, but the agitprop flags and banners had all been left out for the forthcoming May Day celebrations. Every morning our walk from the Wohnung to the university was wallpapered with agitprop.

Schaeffler still found himself under fire and Dr Hentschel was becoming ever creepier. He opened his class this week by reprimanding David, my roommate, for taking himself off alone to Rostok and staying with a local family. This was not allowed. Two things struck me at this moment. I thought David had been a little naïve and reckless – he may well have caused trouble for the family – but I was more intrigued by how Dr Hentschel knew about it. And this was where we got our first practical insight in the activities of the Stasi. Hentschel was momentarily silent, staring at us all and grinning in a rather unappealing manner. He then took great delight in describing in detail what each of us had been doing and where we had all been in our free time since arriving in the DDR. It was excruciating. When he’d finished, in a completely off-the-cuff manner, Dr Hentschel then informed us that our country, together with the USA, was now at war with Libya. We were all suitably alarmed, though, rather cruelly, he would reveal no more.

After the class, I went to the main post office to book a telephone call to the west. Such calls had to be booked in advance and could only be made from designated booths within the post office building itself. I was given an appointment for the next day. At the appointed time, I sat in a booth and dialled home. My mother’s voice sounded very far away and there was a noticeable delay on the line. We exchanged pleasantries and I let her know that all was well. When I asked her about what was happening in Britain with regards to Libya, a man’s voice came on the line for about ten seconds or so. He shouted something I couldn’t make out and then the line went dead. I stared transfixed at the receiver, and held it to my ear again, but there was nothing but static. When I emerged from the phone booth, the post office was going about its daily business as usual. I assumed the man who had been listening in on the call and terminated it was somewhere in the building, but as with all things Stasi, it was hidden beyond view. Rerunning it in my head, I hoped my mother had simply assumed it was a crossed line and nothing more sinister.

Dresden and Meissen

At the weekend, some of us decided to take the train to Dresden and Meissen. We were, after all free to make such trips. After his dressing down by Dr Hentschel, my roommate David was feeling a little sorry for himself, so we invited him along. He came, but didn’t stay long. He was clearly troubled by recent events.

I’d been reading Vonnegut’s version of the firebombing of Dresden so wasn’t surprised to see much of the city rebuilt in Soviet fashion – wide avenues and rather uninspired apartment blocks. But there was something about Dresden that captivated us. We wandered through the fabulous Gemäldegalerie and hung out on the Augustus Bridge spanning the Elbe. Also lovely were the narrow winding streets of Meissen – famous for its porcelain – and, for a couple of hours, we seemed to have this lovely place almost entirely to ourselves.

Now, fully aware that we were being followed, we couldn’t help looking over our shoulder every now and then, but I think we were being naïve expecting to see shady-looking men in trench coats. There were informers everywhere. Looking back on it, I don’t think this awareness changed our behaviour any. In fact, we were quite relaxed about it. The only time I recall being conscious of it was when I interacted with people – either wondering whether the conversation would be reported or making sure I didn’t get anyone into trouble.

Though we didn’t know it, and wouldn’t for several weeks to come, on Saturday April 26, while we were in Dresden, the Number Four RBMK Reactor at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl, Ukraine, exploded.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Five.

Völkerschlachtdenkmal

I had a chat with a sports teacher in a bar called Zensies that we had discovered. We talked about football (the World Cup was about to kick off) and life in the DDR. He was interesting to talk to because, although he didn’t really swallow all the agitprop and knew there were real problems in the DDR, he also saw positive aspects of life here. He could even see the bright side in having to wait up to 12 years for a Trabant car. The DDR lacked materialism and greed, he argued. There was no unemployment and no ‘keeping up with the Jones’ here. He told me he was terrified of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher – so at least we had that in common. I never really knew who I was talking to in the DDR. After a month here, I was beginning to get to grips with life behind the Iron Curtain, and part of that was understanding that some people were not all they seemed. But I’d made up my mind to try, wherever possible, to take people at face value.

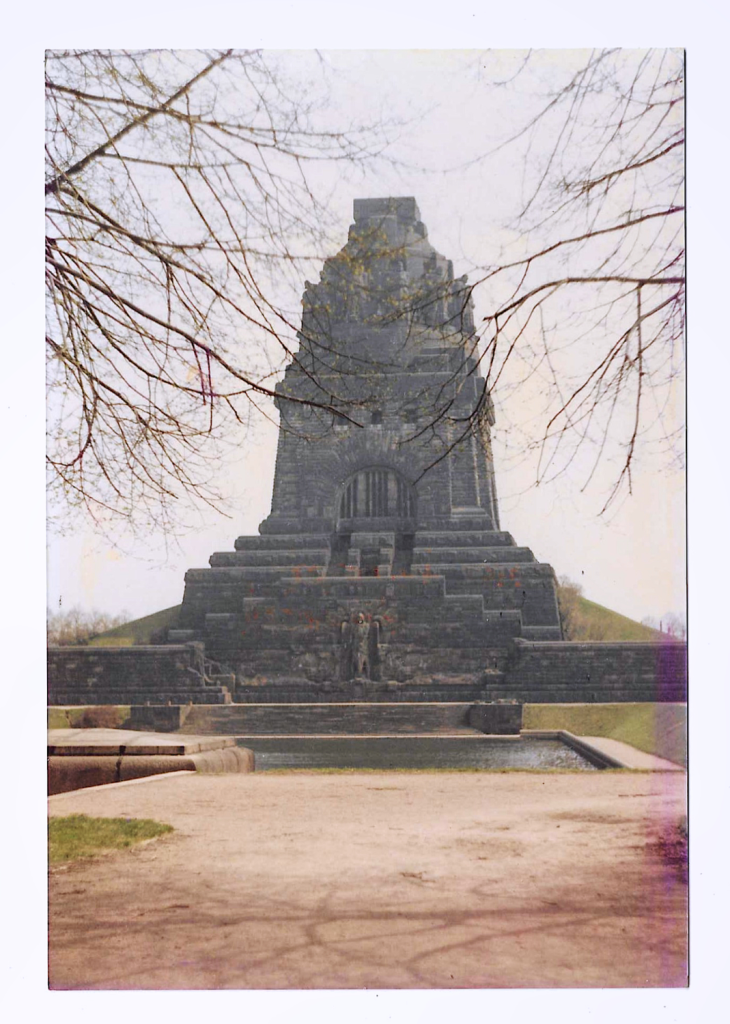

Our Landeskunde excursion this week was to the Völkerschlachtdenkmal (monument to the 1813 Battle of the Nations or Battle of Leipzig, when Napoleon’s army was defeated). I found the monument really quite stirring (I could easily imagine Wagner’s Götterdämmerung playing when I saw the16 giant warrior knights standing guard in the crypt). After a long climb up a steep spiral staircase within the granite walls, we reached the top and enjoyed expansive views. I loved it. As expected by now, the history of Napoleon’s defeat at Leipzig was compared to the defeat of Nazism by the antifascists of the east and a warning to be on guard against imperialists of the west (that would be us).

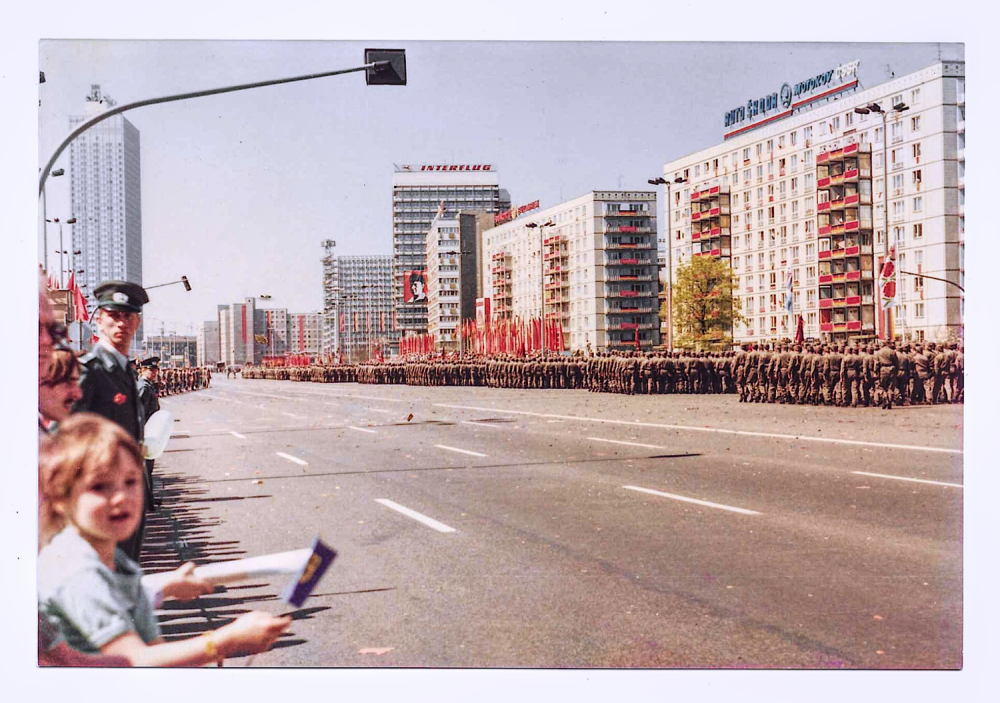

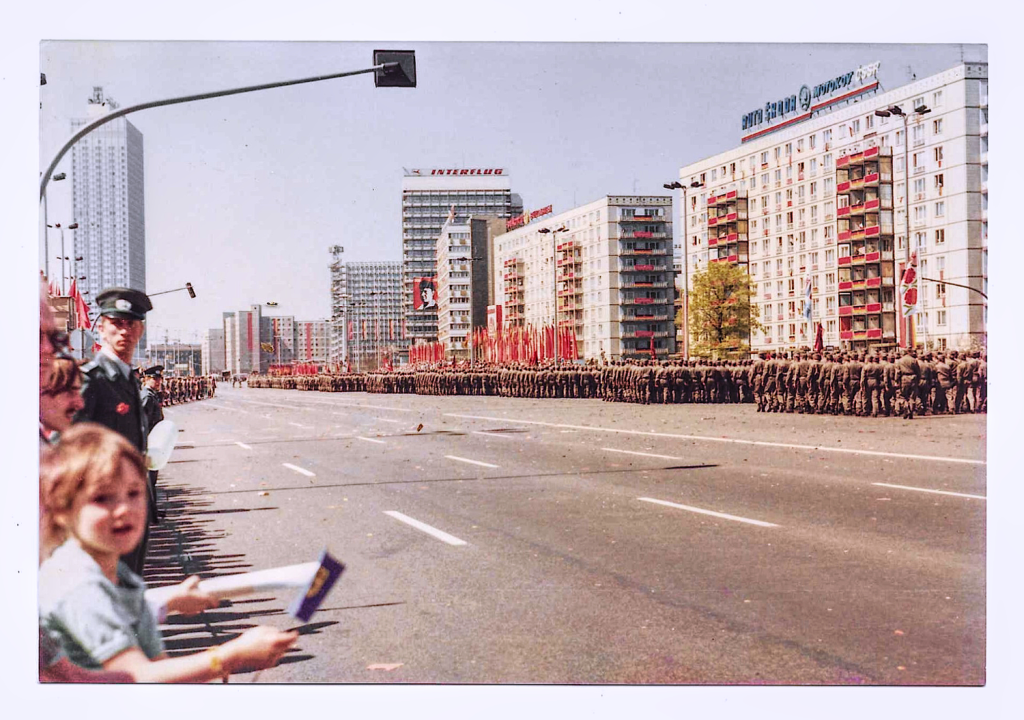

May Day Parade in Berlin

On Thursday 1 May, Trasy, Vonny and I took the 6am train to Berlin and by 9am we were stationed on Karl Marx Allee ready for the May Day parade to start. And once it did, it seemed endless. From ordinary citizens carrying banners to the might of the Soviet Bloc military, it was a spectacular that we knew we would remember forever. Passing and saluting Erich Honeker and members of the Party hierarchy, the parade carried an extremely strong socialist and anti-west message. Slogans on huge banners as well as shouted by those around us included “Hoch! Hoch! Hoch!” (Hoch means high), “Eine Welt Ohne Kernwaffen” (a world without nuclear weapons), Der unzerstörte Bruderbund mit der Sowietunion – Fundament unseres Fortschrietens” (Our unbroken brotherhood with the Soviet Union – fundamental to our forward progress), and “Danke Erich Honeker”.

When the parade had passed, we strolled under a hot May Day sun along Karl Marx Allee to the Brandenburg Gate where we were photographed by fellow westerners standing atop viewing platforms on the other side of the wall beyond the death strip. That felt really weird. We found a shady spot in Alexander Platz and whiled away the rest of the afternoon before catching a train back to Leipzig.

Torgau

The hot weather continued into the weekend. I took a train with Vonny to a town called Torgau on the Elbe. A historic place known for Schloss Hartenfels and surviving renaissance and gothic buildings, it’s noted as the place where US and Russian forces met in the second world war. It was a lovely town but it felt rather like being on the set of a Sergio Leone western – hot and still, flies buzzing, one or two locals dozing in the shade. After exploring the town, we walked down to the river where we found a grassy spot in the shade and dozed for a while. Waiting for a train back to Leipzig, we found a coffee shop in the Rathaus (town hall) and tried to guess which of the locals were spying on and making notes about us.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Six.

Gewandthaus

The week began with a classical music event at the Gewandhaus (concert hall) in Leipzig. It was in two parts. The first was a performance of Shostakovich’s Symphony Number 14, Op 135. It’s noted as an especially dark work, a meditation on death. And it felt like it. The second part of the concert was a modern DDR composition by Karl Ottomar Treibmann who was professor of music theory at the Karl Marx University. I don’t remember the title of the piece that was performed, but I do remember longing for it to end.

There was no escape from the Gewandhaus, it seemed, for it was also the subject of this week’s Leipzig Landeskunde excursion, and so we were back the next day. We were given a tour of the building and a lecture on its history (the original Gewandhaus was constructed in 1871) and notable premiers there included Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5, Schubert’s Great Symphony, Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, and others. This was the third iteration of the Gewandhaus, however. Constructed in modern soviet style in 1981, it would be noted as a forum for political dissent during the revolution of 1989 – just three years on from the presentation we were attending.

Berlin and Potsdam

On Friday, accompanied this time by Dr Hentschel, we travelled by train to Berlin on the second Landeskunde of the week.

He led us on a full-day city tour that included a trip to the top of the famous TV Tower (Fernsehturm) where we were able to see across the wall into West Berlin, and Marx Engels Platz. After a rather forgettable lunch at the Berlin University canteen, we went to the former home of Bertold Brecht – without doubt the highlight of the tour for me. As a Brecht fan, I loved it. The house was lovely. We meandered through his library and office, even around the quaint garden. We saw his fittingly simple gravestone at the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery along with those of other famous artists and personalities such as Heinrich Mann and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

Next up was an art gallery tour of contemporary DDR art, which I enjoyed, followed by watching the changing of the guard at the Anti-fascist Memorial, and Brandenburg Gate – again being observed and photographed by my fellow westerners from their viewing platforms beyond the wall.

The evening was a treat. We dined at a restaurant at the rear of the Berliner Ensemble that was usually reserved for performers. Then, at the Berliner Ensemble itself, we saw a musical production by youth members of a Berlin music school. I’d always wanted to come here and, though disappointed not to see a Brecht play, it was nevertheless quite a moving experience for me. Established by actress Helene Weigel and her husband Bertolt Brecht in East Berlin in 1949 (before the construction of the wall), many of his plays have been staged here.

We overnighted at a city youth hostel and were up and off again at 7am. Sadly the train we were meant to catch to Potsdam wasn’t running so we didn’t arrive until late morning. Dr Hentschel led us to the stunning Sanssouci Palace, Frederick the Great’s ‘no worries’ summer residence. After a tour, we were given a little free time to enjoy the magnificent gardens and park before heading to Cecilienhof Palace, also lovely, and famous for the Potsdam Conference of 1945. The tour was interesting, though rather rushed. After refreshments in Potsdam, we had a tour of the Filmmuseum in Potsdam’s oldest building, the Postdamer Stadtschloss (an interesting tour of the Babelsberg film world – also a bit rushed) before catching the late train back to Leipzig. We were worn out. Despite all my misgivings about Dr Hentschel, there was no denying his commitment to this culturally rich two-day tour of Berlin and Potsdam. Coupled with the May Day parade, my experience of DDR Berlin had been a memorable one.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Seven.

Professor Knight

On Monday of week seven, Hashi and I went to the Interhotel am Ring to meet and greet Professor Knight. As well as being my personal tutor, Professor Knight headed up the German department at the University of Leeds. He was here for a few days to see how we were getting on. It was also his 65th birthday and he was due to retire.

I had a soft spot for Professor Knight. He had been very helpful and supportive to me and was also my Marxism class tutor. On Tuesday, after he had rested from his journey, he took us out for dinner at the Thuringer Hof restaurant which had become one of our regular eateries in Leipzig. It was a fun evening. He was eager to know what we had been doing and how we had been faring under the regime. He was impressed by how much we had done and reassured us that the classes we were taking at KMU were not as important as the experience itself. He also advised us to be respective but also wary of Dr Hentschel. It was common knowledge that the Franz Mehring Institute was a Stasi organ to ensure compliance with the party message throughout KMU, and that Dr Hentschel himself was likely a high-ranking officer.

For our part, we were eager to hear the western version of what had happened regarding the bombing of Libya, and were the rumours of a nuclear explosion in Kyiv true? Professor Knight cleared up the details regarding the US bombing of Libya from the UK and reassured us that our country was not at war with anyone. On Chernobyl, details were sketchy. He said he had received a formal request from the British government to take us out of the DDR because of the potential for nuclear fallout, among other things, but that it was entirely up to us if we stayed or left for home. None of us wanted to leave which brought a smile to his face and he just nodded. It had been a memorable evening, and we were all grateful for his visit. Professor Knight would stay for another day and then head back to England. I never saw him again. He did indeed retire in 1986 and died just a year later.

The rest of the week was routine. There was no Landeskunde excursion, just regular classes. Schaeffler managed to get a few points across for a change, but Rainer, our German language tutor, continued to spend the entire class asking us questions about life in the west.

It was still incredibly hot. We speculated about nuclear fallout, and asked Dr Hentschel about it, but he just smiled and refused to speculate on Chernobyl. The truth was that he probably didn’t know many details of it until on or slightly before 15 May when the Neues Deutschland newspaper printed an announcement in full by Michail Gorbachev, leader of the Soviet Union. It was the first time there had been any official acknowledgement of the accident, in print at least, but there was no information at all about the possibility of people being affected beyond the immediate disaster zone. We hoped our slowly bronzing skin was due to the heatwave and nothing more sinister.

At the end of the week, we tried out the cinema and saw Eisenstein’s 1925 silent classic, Battleship Potemkin, which irony of ironies, was banned in the UK for the longest period of any film in British history.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Eight.

Weimar

On Tuesday 20 May, we caught an early train to Erfurt and then, via Ilmenau, on to the lovely village of Stützerbach on the margins of the Thuringian Forest. After lunch, we visited the Stützerbach Goethemuseum – a former glassblower’s house where Goethe stayed some thirteen times between 1776 to 1780. It was a charming and ornate place in a lovely, forested setting. I can imagine why a writer might want to stay here and wander the forest trails as he did.

Speaking of which, we then set off on what has become known as the Goethe Trail between Stützerback and Ilmenau. It’s a 20km forest trail and offered up lovely views, valleys, babbling brooks – all a Weimar Classicist could ever need.

We had a forgettable meal in Ilmenau and, though weary, rather enjoyed a comedy at Weimar’s Deutsches Nationaltheater called Stadelmann by Hans Lucke, an East German actor/author. We were tired though, and the theatre was hot, so it was hard to concentrate on the German properly.

After the performance, we went by bus to a holiday camp where we would be based for the week. We shared it with other students from the Soviet Bloc, mostly Poles, who proved to be great company.

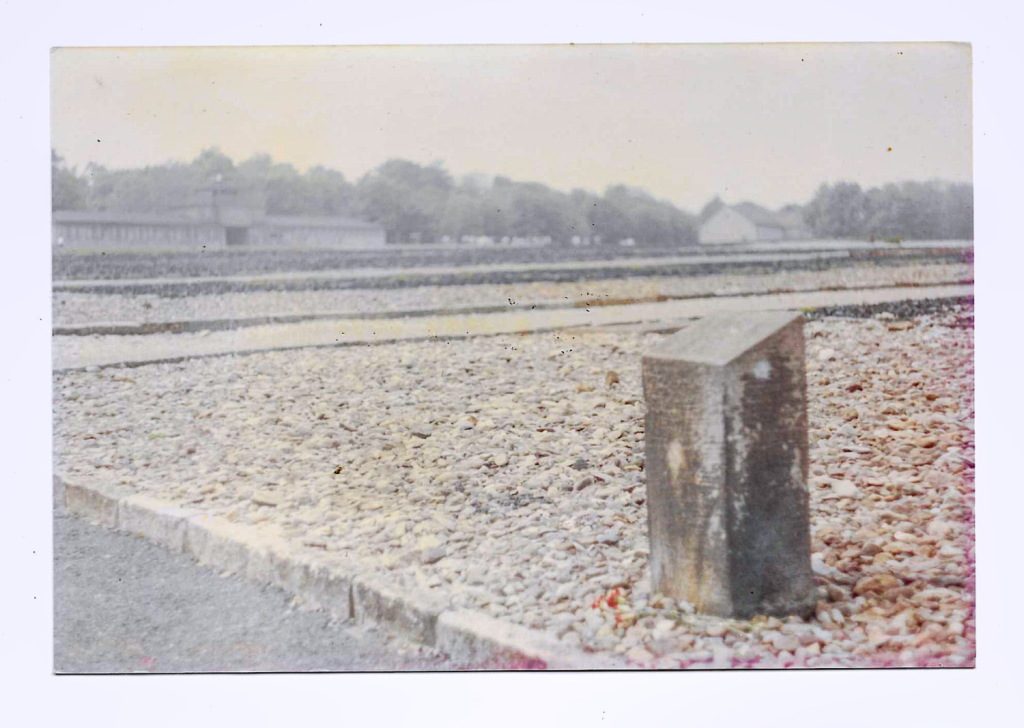

Buchenwald

In the morning, from our camp, we went to Weimar and then walked for about an hour along a lovely forest trail to an altogether different camp. We knew we were there, or at least walking around its perimeter, from the rusting metal fence and barbed wire that were now visible through the undergrowth. As we walked, the fence and wire became more prominent until we could see the camp properly. It was a vast open area. All the wooden buildings had been taken away and, in their place, memorial stones had been erected. At the main entrance to the camp was a small interpretation centre where we were shown a film about its history. The documentary was disturbing, as you would expect, but two things really struck me: firstly, all of the camp’s victims were referred to as antifascists; secondly, the film ended with a short sequence showing the US war in Vietnam, and imagery comparing the victims of that war with the victims of this place.

I had picked up a guide to the camp. It was in English, which I found surprising. Here’s a short section from it:

German antifascists were the first victims of the nazi regime. The first foreign prisoners arrived at the concentration camps in 1938. With the beginning of the war the number of prisoners increased from month to month.

The fascist troops were followed by the German monopolies which plundered the occupied countries. Millions of citizens were deported. Wild terror was unleashed to break down patriotic resistance. The concentration camps were a mirror of bleeding Europe.

And here, the text of the introductory page:

The concentration camps were set up by the nazi regime to break the resistance of the German people to the fascist dictatorship and war preparations. Unyielding, firmly convinced of the justice of their cause and its ultimate triumph, they did not abandon their struggle. They embodied the better Germany, they salvaged the honour of the German nation. The SS terror was faced with an international resistance movement, headed by the communists. The antifascists in this camp made their contribution to the triumph of humanity over barbarity.

This was an example of the revision of national history that Shaeffler had talked to us about in the context of Die Entwicklung der Persönlichkeit des Menshen. I had wondered how the DDR handled the fact that its own population had been complicit in the atrocities of the war, and here was the answer. They described Hitler and the nazis in a way than made it seem as if they were not German at all and that the communists and antifascists ‘embodied a better Germany’. The post-war manifestation of that ‘better Germany’ was here in the DDR, with its opposite in the west.

After the film, we were faced with the main gate of the camp and the ominous sign above it that read Jedem Das Seine (to each his due).

Inside the camp, its vast scale was immediately apparent. Although all the prisoner barracks had been removed, some buildings remained: admin and stores (now the museum), the officer’s bunker, and the crematorium. Buchenwald wasn’t an extermination camp like Auschwitz or Dachau, it was instead a work camp. The result was inevitably the same. Able prisoners worked in arms and munitions factories, those who became too weak or ill were sent to extermination camps. Those who died at the camp, either through disease, starvation, or a bullet, were cremated in the camp’s ovens. The holocaust has been well documented, so I won’t describe it all here. The camp experience was both moving and sickening.

The camp also has a memorial to former communist leader Ernst Thälmann, a DDR icon along with Marx, Engels and Lenin, who was shot and then disposed of in the crematorium’s ovens.

After the camp, we visited the memorial to the victims of fascism and then met one of the camp’s few survivors, Ernst Jende. Ernst was the leader of an underground military committee and member of the Erfurt antifascist resistance during the rise of the nazis. He was interned in Buchenwald from 1938 to 1945 when the camp was discovered by US forces. He still had a fire in his eyes as he shook his cane, reliving the day the survivors were liberated.

Because of its unfathomable horror and DDR’s retelling of history, Buchenwald was an experience I’ve never forgotten. Many of my photographs may have faded, but my memory of it hasn’t.

Students from other nations (Poland, Russia, Hungary, North Korea, Syria and Afghanistan) had come with us on the excursion and we all got together back at our campsite. There were some interesting conversations fuelled by Hell beer. One of those conversations was with a guy from Kabul. The Soviet-Afghan war that had begun in 1979 was still ongoing with Russians fighting alongside the Afghan military against Afghan Mujahideen rebels. He was coy about his affiliations, but he did say this: The Russians will say they were invited in by a communist faction in Kabul. But I’m from Kabul and I say we were invaded.

Weimar and Jena

We spent a good deal of Thursday and Friday in and around Weimar. Most of the tours were, unsurprisingly Goethe-centric. We went to Goethe’s house, the Goethe Museum, and the place where he undertook his natural science studies – which was lovely. We went to the Goethe-Schiller Archive where we were given a tour and lecture by Professor Karl-Heinz Hahn, a notable expert and SED party member, and finally the Goethe-Schiller memorial.

In the afternoon, we took a bus to Schloss Tiefurt and enjoyed its beautiful gardens (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site). In the evening, back in Weimar, we met and chatted with the widow of political poet Louis Fürnberg (who penned the official SED Party song, famously known as The Party is always right). She was lovely and ran the Louis Fürnberg archive in Weimar.

On Friday, we were back in Weimar on the Goethe trail, this time at his riverside garden house, again lovely. After that we went to and had a lecture on Weimar’s central library, which was a little dry. We had lunch in Weimar and then went by bus to Grosskochberg’s moated castle. This was the former home of Charlotte von Stein, Goethe’s famous muse.

On Saturday, we checked out of the camp and took a train to Jena. After the sun and the heat, we had been experiencing, we were greeted in Jena by a heavy downpour. This worried us a little as we had no idea if we were being subjected to fallout from Chernobyl. But we soldiered on through the rain with plastic bags as makeshift coats. Gill and I walked around with Frau Sander’s spare coat over our head but got soaked anyway. As we were trudging through the rain towards Schiller’s former home, Frau Sander declared: Well, you can’t blame the weather on communism!

I enjoyed the art in Schiller’s house, and we all enjoyed a break from the rain. It was clear to most of us by now, however, that we were pretty Goethe-and-Schillered-out. German Romanticism and Weimar Classicism have never been my favourite German artistic periods, so I’d also had my fill. Given the weather continued to be unforgiving, it seemed like a good time to visit the Karl Zeiss Planetarium which was heavy on Soviet achievements and light on the cosmos. But dry at least.

We grabbed bratwurst at Jena railway station while waiting for the train back to Leipzig and all agreed that though tiring and an assault on the brain, the senses, and the emotions, this Landeskunde week had been exceptional and we made a point of thanking our tutors who also looked rather worn out.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Nine.

A strange familiarity

A strange familiarity with DDR life had set in and our routines and surroundings no longer seemed quite as alien to us as they had been in the beginning. We were comfortable at the university, we knew the city well, and we accepted the fact that our movements and interactions were being recorded. On sunny afternoons, we chilled out on the playing field behind the Wohnheim, reading, chatting, listening to music, sunbathing. Most of us were now having to watch the finances so our independent outings had been curtailed somewhat and we were once again eating in the university Mensa.

On Tuesday, Frau Sander took us on a Leipzig Landeskunde trip to the Dimitrov Museum. Apparently, it was the largest museum in the DDR that was dedicated to a single person. Georgi Dimitrov was a Bulgarian communist who, after the Reichstag fire of 1933 was put on trial along with three other Bulgarian communists and Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutch communist who had purportedly been discovered in the building. All were accused of plotting and carrying out the arson. Though it was essentially a political show trail, Dimitrov mounted such a strong defence against the main prosecutor, the nazi Hermann Göring, that the Bulgarians were acquitted. Van der Lubbe, however, was found guilty and executed. The DDR had turned the story into a propaganda piece on a massive scale. We were given a guided tour of the exhibition and then we listened to a recording of the trial itself.

On Thursday, we went by train on a second Landeskunde trip to the town of Altenburg. It was an historic ‘Barbarossa town’ with a castle. Famous also as the place where the popular German card game, Skat, was invented, it made perfect sense for us to be taken on a tour of the playing card factory. As the tour was given by Altenburg high school students, and lacked any political dimension, it was fun and interesting.

In the evening, Gill and I headed to downtown Leipzig for food and drink at a new bar we had discovered called the Journalisten-Klub which, as you might expect, was a popular hangout for journalists.

On Saturday, a few of us travelled by train to the city of Halle where the Händel-Festspiele (the annual Handel classical music festival) was taking place. We managed to get in to enjoy a choir performance in a beautiful church which was excellent, but sadly because of the heavy rain, the firework display to mark the climax of the festival had to be cancelled.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Ten.

Student Party and thoughts of leaving

The rainy weather continued into our tenth week, and the Leipzig Landeskunde outing was called off. Our classes continued in the same vein but there was definitely a hint of them beginning to wind down.

In our Wohnheim, there was a small bar and recreation room with a black and white TV. We’d been up there a few times in the evenings for a drink and to watch some of the World Cup. It was also a great place to mix and chat with DDR students and, although we made some friendships, there was always the feeling of a divide. Sometimes I felt like I was talking to people who were trapped and desperate to escape. One student even speculated that if I made her pregnant, it might be her ticket out of the East. So, occasionally, it was a bit intense in there, and even the regular barman – a student by the name of Thorsten – suggested that I tell some members of our group to be careful with their interactions. He admitted to me right off the bat that he was expected to report conversations. Despite this, it was a convenient place to hang out in the evenings if we didn’t fancy the trip into the city. And the rain had put paid to that this week.

Some of the group had already begun to make plans to leave the DDR and head back to the west. It was up to us when we chose to do this – we weren’t compelled to see out the full twelve weeks – and a few had already decided that they were just about ready. This led to the idea of a party on the Friday of week ten. The booze and snacks were on us. Some of us had been shopping – even to the Intershop which only sold western goods at a truly exorbitant price. We made a rather deadly fruit punch, had plenty of chilled Hell beer, western cigarettes, chocolate bars and music. The idea of chocolate bars came from an evening several weeks before in the bar when someone had been surreptitiously sharing slices of Mars bar wrapped in silver foil. It was a boozy evening, and, though I don’t remember that much about it, for a change, the conversation had felt free and easy.

It was difficult to forge close friendships with some of the DDR students because I knew I would be leaving. And it didn’t feel like just regular ‘leaving’ – there would be a finality to crossing back to the other side. We would really miss DDR friends like Babette and Claudia, who had been close to our group throughout our stay. It didn’t feel right.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Eleven.

Departures

Some of the group left at the beginning of this week. Schaeffler’s class was therefore suddenly far more open to discussion, and we talked about all manner of things. I’d become very interested in the whole concept of Die Entwicklung der Persönlichkeit des Menschen to create a DDR identity. Sure, our classes, the literature, the Landeskunde excursions, the history and the culture had all been full of examples of this policy, but, beyond academia, I’d experienced situations where people were fully aware of but not in concert with SED political ideology. It’s easy for me to say this with the benefit of hindsight, but I felt strongly at the time that, although sympathetic to a socialist societal model, the version of socialism in the DDR with its Orwellian propaganda, agitprop, redefinition of history, and a society saturated by surveillance and fear, could never succeed. Wolfgang, the Polish journalist I’d met on the train to Bad Frankenhousen, had been right. The only thing that was real in the DDR was its darkness.

Wednesday was Gill’s last night and the two of us hit the city. We drank in a couple of bars and then strolled around empty streets for much of the night and didn’t get back to the Wohnheim until after 4am. Bleary-eyed, we headed down to Leipzig Hauptbahnhof where she caught the 9am train to Cologne via Marienborn – the route we had taken over ten weeks ago.

Back to Dresden

Though by now much depleted, our final Landeskunde excursion was to Dresden, a city we had enjoyed earlier on an independent trip. Happily, Vonny, Trasy, Cate and Hashi were still here so we enjoyed our last outing together under the supervision of Dr Hentschel. We perused the gallery of old masters once again and then had lunch which, to our great delight, contained a tomato salad!

We took a short riverboat trip up the Elbe to Pillnitz where we explored the restored renaissance castle and its grounds before heading back to Dresden and a tour of the city’s surviving historic landmarks. On the train back to Leipzig, we presented Dr Hentschel with a bottle of whisky we’d bought from the Intershop and shook him by the hand in thanks for all his efforts in helping to make our DDR experience so memorable. He actually seemed quite moved. On arrival in Leipzig, we said goodbye. I never saw him again.

What happened to Dr Hentschel after the wall came down in 1989? Details are sketchy. The Franz Mehring Institute was closed down, and academics and party members such as Dr Hentschel left their posts and quietly disappeared into obscurity. I found tentative evidence that he continued to live in Leipzig until his death in 2012, but I’ve not been able to corroborate or confirm this, likely as it seems.

Iron Curtain Diaries: Week Twelve.

The last to leave

On Monday morning, I was up early to help Trasy, Vonny and Cate get to Leipzig Hauptbahnhof. They were heading back the way we had come, via Cologne. We said our fond farewells and the train pulled out on time. Why hadn’t I gone with them? I had a friend in West Berlin – Henrik – whom I’d known since high school, and I was planning on spending a few days with him and his family before heading home too.

After seeing the girls off, I walked to the police station to ‘abmelden’ – to officially sign out of the DDR system and let them know my departure details. It was a lot easier than it had been to register almost three months ago. I would leave at the last possible moment, on Friday.

In the meantime, as there were no more university classes, I was determined to fill my week with activities. So I made my own Landeskunde trips. I went back to the Völkerschlachtdenkmal, which I’d enjoyed so much the first time, and enjoyed the views of Leipzig from the top. On Wednesday, I took a train to the town of Colditz where I wandered around until I found the Castle. An infamous prisoner of war camp made famous by a BBC TV series and even a board game that I played as a child, it now served as a sanitorium. Unchallenged, I ventured inside and wandered around the courtyard. It felt like the place had been abandoned. I escaped easily enough.

On Thursday, I met up with Babette, one of our DDR student friends. We had a coffee in the city then walked back to Tarostrasse where we said our goodbyes and I packed my battered old suitcase. Instead of toilet rolls, I had all the memorabilia I’d collected.

On Friday, Hashi and I took the 8.18am train from Leipzig to Berlin. We were the last to leave. She was heading to Dusseldorf via West Berlin. We planned to cross into West Berlin via the Friedrichstrasse checkpoint.

We were the only two in line. She went first then, a few minutes later, they called me. I handed my passport to the officer in the booth and he carefully examined it. Then he showed it to a colleague and a discussion ensued. Something was clearly amiss. I was then instructed to follow two uniformed border guards into what I can only describe as an interrogation room. I was told to sit at a desk. Another uniformed officer sat opposite me and examined my passport. A second and a third came in and they all looked at it together. By now, I was feeling a little nervous and several ‘what if’ scenarios were racing through my mind. Then, the man sitting opposite pushed my open passport towards me and told me I needed to update it because my photograph didn’t look much like me. He was right. I’d had the passport since high school and the photo was old. There followed a lingering silence and then a smile. He told me I could leave. The two other guards were also smiling. They had had their fun.

Out the other side, I was hugged by a visibly shaken Hashi who wondered what on earth had happened to me. Once we had both calmed down, we caught the train to Kurfurstendamm station and went to Cafe Kranzler where we enjoyed our first western food in three months. It was a strange feeling looking out into a vibrant and bustling West Berlin.

Hashi and I said our goodbyes and I got on a bus to Kladow where my friend Henrik lived.

In all, I spent five days exploring West Berlin, including climbing the viewing platform overlooking the wall near the Brandenburg Gate. Across the death strip was East Berlin, beyond it the DDR, and a whole lot of memories.

On Thursday 26 June, I caught the noon train from West Berlin to the Hook of Holland. It was a ten hour journey back across the DDR and West Germany. Feeling very much alone now, I sat in the all-night ferry bar until we reached England at 6.30am on Friday 27 June where my father met me and drove me home.

Postscript: 2025.

In October 2025, I went back to Berlin for the first time since 1986. Although the DDR hadn’t existed since 1989, I wondered if any traces remained and whether I would still recognise them. Of course, in that time, much has changed. With liberty came capitalism, in waves, and I was reminded of all the lectures we’d had about protecting the DDR from exactly that when I saw a Starbucks in the place I’d once stood for a photograph on Unter den Linden, and a MacDonalds at Alexanderplatz station. West Berlin had spread into East Berlin in a tsunami of designer brands and boutique coffee shops selling matcha tea – all the way along Unter den Linden through Museum Island to Alexanderplatz – which had transformed from cold soviet to tacky touristic.

I walked through the Brandenburg Gate in awe that such a thing was now possible, and couldn’t resist touching its columns each time I did so. I looked for the statues of Marx and Engels and eventually found them surrounded by piles of earth on a building site. I walked all the way along Karl Marx Allee where we had watched the 1986 May Day parade and was happy to see that the wide tree-lined avenue remained with its classic soviet style apartment blocks – now looking majestic in comparison to the ubiquitous glass office towers being erected nearby. Instead of marching soldiers and trabants, there were swanky cars and near empty footpaths. Agitprop was, needless to say, absent.

I walked to the end of Karl Marx Allee, through the Frankfurter Tor, and along Frankfurter Allee until I reached number 204, home of the Stasi archives building. Inside, I was met by friendly staff and my now rusty German was tested as I explained how I’d studied at the Karl Marx University of Leipzig with fellow students in 1986 under the supervision of Dr Johannes Hentschel, and that our movements and interactions had been recorded. They took all my details and, if files still exist on me, I should hear from them within a couple of months. If any are found, I’ll post them here.

I sought out and found Berthold Brecht’s house which you can still visit but by appointment only. In the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery next door to the house, I revisited his grave and paid my respects. A stark reminder of the years that had passed hit me when I took a photograph of his front door. In 1986, I had done the same (see above), with Gill standing on one side and Vonny on the other. This time, the door was closed and my friends were no longer there.

Fittingly, one of the last things I did in Berlin was visit the Friedrichstrasse crossing which has been preserved as a museum called Palace of Tears. Inside were the booths that we had to enter to cross the border, and where I had been briefly detained because of an old passport photo. Walking into and through the booth again gave me the shivers.